Seeing Yourself the Way Someone Else Does Is Not a Personality, It's a Virtue

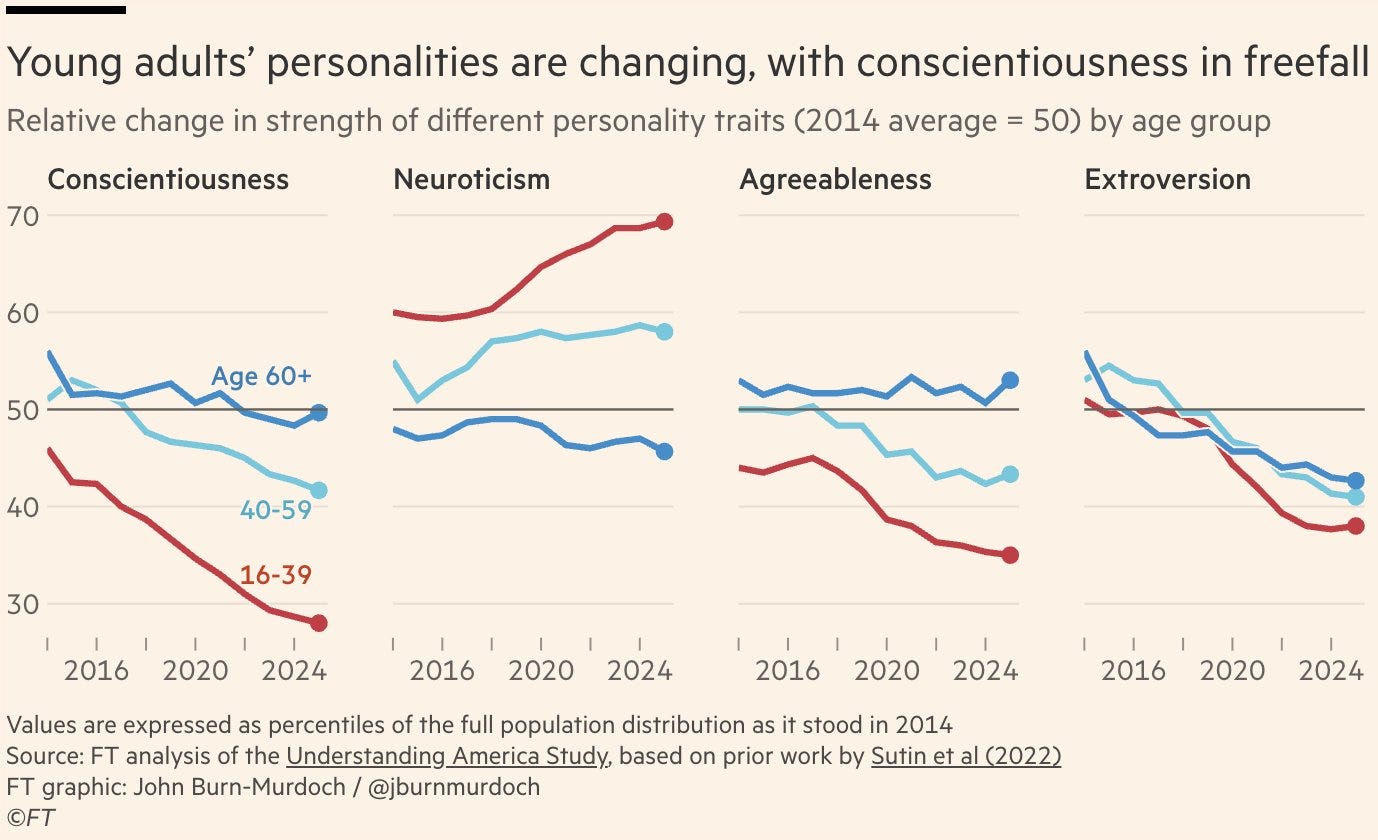

This article, and an accompanying X thread, have been widely shared among my circle. The gist is plain enough: Younger Americans are losing the interest and possibly the capacity to see themselves the way other people see them.

That’s at least how I define “conscientiousness,” and it seems to accord with some of the behaviors that are used to exemplify …