The Matrix is Not the Cultural Metaphor We Need

There are no supervillains above the surface. There is just us.

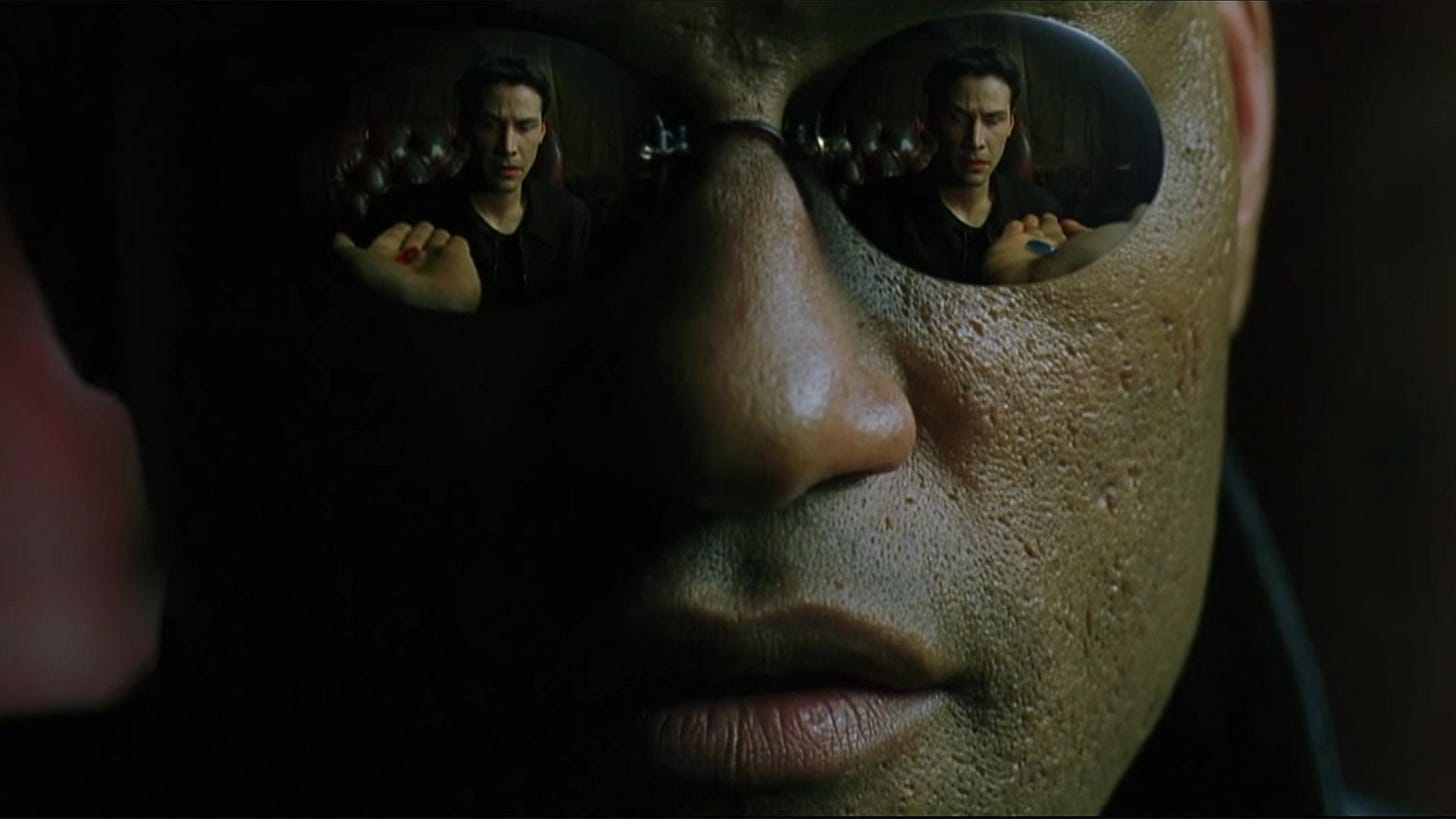

Have you noticed how The Matrix has become an existential metaphor for certain folks? Andrew Tate, the repugnant but extremely popular influencer who targets young men, tells his audience that “the matrix” is why they feel frustrated, alone, ineffective, and adrift. For Tate, the matrix seems to be the ambient society of capitalism and feminism. Like th…