We Can't Talk About Purity Culture Without Talking About the 1990s

Our parents got a lot wrong, but they didn't have it easy

Note to Readers: Today I’m re-publishing this piece from November 2021. I was recently a guest on Trevin Wax’s podcast Reconstructing Faith, where I spoke about some of the ideas in this post. If you want to listen to what I said, check out the podcast here. My thanks to Trevin for his kind invitation.

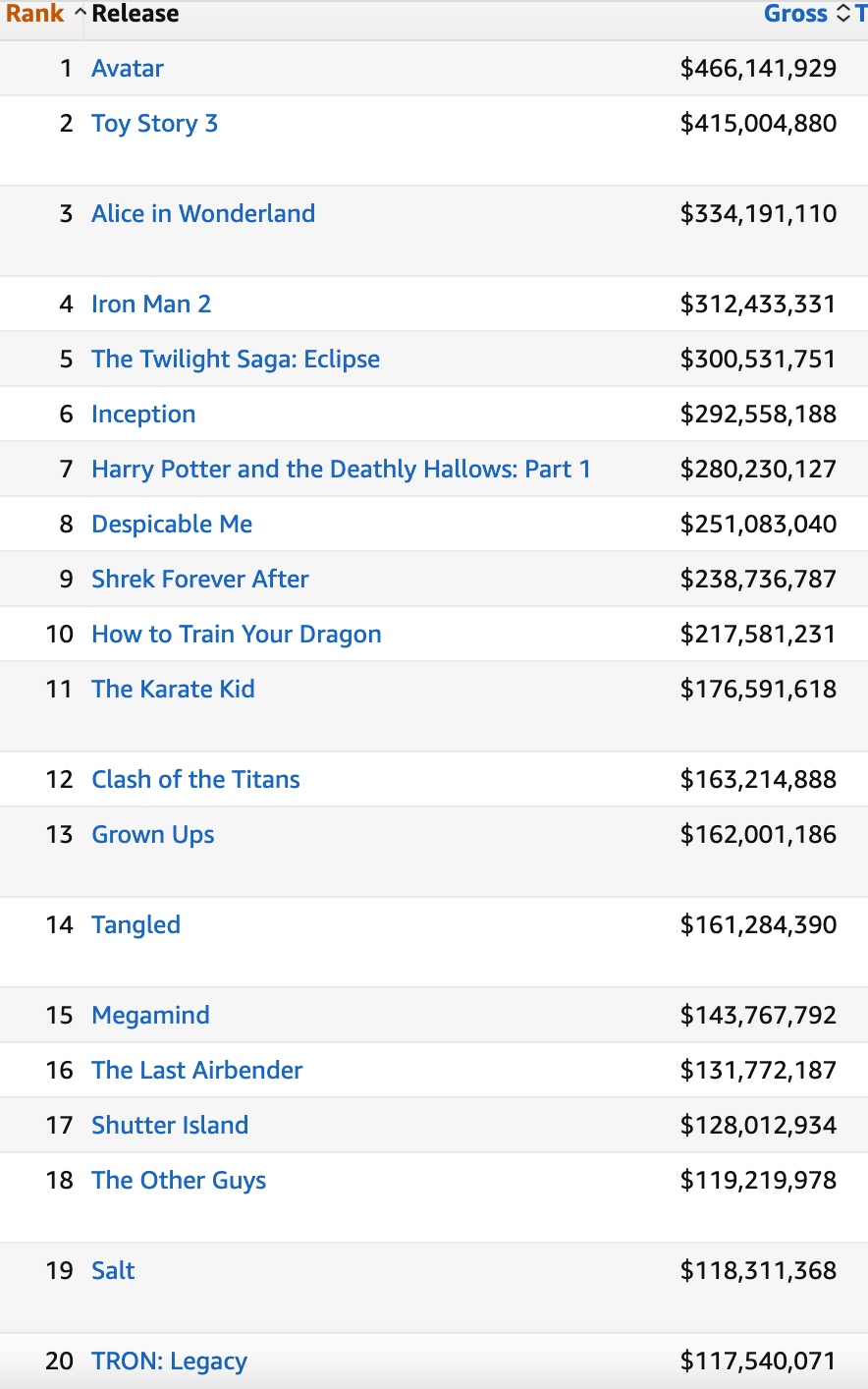

Take a look at something I find pretty interesting. Here are the top 20 grossing films of 2010:

Now, here are the top 20 grossing films of 1999:

In the top 20 list from 2010, there are 3 R-rated films: two comedies and one drama. In the list from 1999, there are 7 R-rated films, including one teen sex comedy, in addition to the PG-13-but-still-pretty-racy Austin Powers film. The formula generally holds, by the way, if you go forward from 2010 but backward from 1999. The 2010s did see a couple successful hard-R comedies (Bridesmaids, The Hangover, and Ted), but the 90s were stuffed full with such hits.

Staying in the same pre-Y2K era, what about Woodstock 99? The music festival in New York was featured in a documentary this year. Particularly in the wake of #MeToo, the festival has become infamous for its eyewitnesses reports of mass sexual assaults. Here’s how The Ringer’s Steven Hyden describes the footage from the festival:

I wasn’t at Woodstock ’99. But I have watched video of the Limp Bizkit performance on YouTube many times. From the video, two things are immediately obvious. First, the crowd was extremely rambunctious and unruly. Some of the misbehavior is typical drunken buffoonery that’s ultimately harmless; other acts are flat-out criminal.

Two random cutaways to the audience show topless women whose breasts were groped by nearby men––men who didn’t, from what I can tell, have permission to touch these women. This happens in shots that last for maybe a second or two each. If it was that easy to capture footage of women being sexually assaulted, I can only imagine how widespread it was.

Much of this footage, by the way, was being aired by MTV. Two things about this matter. First, MTV had been riding the 1990s cable TV surge. Every single year in the 90s cable TV subscriptions—which offered significantly more adult and explicit content than broadcast TV, with much fewer regulations—went up by at least one million subscribers before hitting an all-time peak in 2000, at 68.5 million American subscribers (at which cord cutting began to set in). Second, none of this content was particularly unusual for MTV, which had been an enthusiastic participant in the general coarsening of American pop culture throughout the 90s.

But it wasn’t simply on the movie or TV screen. The 90s saw two massive sexual revolutions intersect with one another. The first was the teen pregnancy rate, which peaked in 1990 and stayed very high for most of the decade. The second was the Internet, whose contribution to the law of diminished erotic returns needs no explanation.

To put it all into perspective: Families in the 1990s were besieged on multiple fronts of American culture by an onslaught of sexual free-for-all, both real and simulated. The 1960s and 1970s may arguably have been more extreme demonstrations of licentiousness, but the key difference for the Boomers was the absence of mass media technologies that put the revolution directly in the living rooms of Americans. Parallel with the ascendant teen pregnancy rate was a pop culture infrastructure that kept pushing the boundaries, kept normalizing ravenous sexual consumption, and seemingly kept inventing new ways for everyone to encounter it.

+++

I Kissed Dating Goodbye is not a good book. The critiques that have become standard against it are mostly just and true. But what is often missing in discussions about it and the evangelical purity culture it seems to symbolize is an explanation of why books like this, Every Man’s Battle, and others seemed to resonate so widely with conservative Christians. If any explanation is offered at all, it is usually that evangelicals are sexually regressive and patriarchal, and these resources accessorize the female body while selling a bill of goods to men caught underneath evangelicalism’s sexual exceptionalism.

This explanation seems especially persuasive when you hear many talk about the errors of evangelical purity culture as if they are blindingly obvious. I’ve yet to read someone’s account of growing up in a legalistic or shame-based evangelical youth culture that also acknowledged that their own sense of ethics has changed or shifted since then. Judging the faults of others back then against our moral vision right now is sometimes necessary, but it can also offer false comfort and a misleading narrative, which can condemn us to merely repeat similar errors.

IKDG was published in 1997. It was written to a conservative evangelicalism that was trying to hold onto abstinence, fidelity, and self-control amidst a society that was seemingly determined to see that no one could. More to the point, IKDG spoke directly into a teen dating culture that had become infected by both widely broadcast smut and by a strange solemnization of adolescent romance. Perhaps cultivated by a divorce rate that had surged to all-time peaks, teen films and sitcoms in the 90s were unapologetic in making their characters talk to each other like husband and wife. The worst offender I know of here is Boy Meets World, a pretty intelligent TV show whose main story arc is the romance between its two lead characters that starts in elementary school and carries all the way into college-aged marriage. Some of the dialogue between 16 year old Cory and Topanga seems designed to communicate a mini-marriage.

The swirling morass of pop culture and societal transformation put a lot of conservative evangelicals on a kind of permanent defensive. How do you minister to boys and men who seemingly overnight have the technology and the social permission to indulge any impulse? How do you navigate the emotions and desires of young women who are presented with two visions of female happiness: fairy tale adolescent romance, or, failing that, limitless sexual availability? To top it all off, how do you articulate a gospel response to all of this if you’re a typical evangelical church in the mid 1990s: committed to pragmatism, skeptical of theology-speak, and measuring your health in terms of numbers and giving?

None of this excuses getting it wrong. Earnestness is not a get-out-of-jail-free card, including for the church. But the narrative of evangelical purity culture has too often depicted the parents, youth pastors, and Christian writers of the 1990s as people who either sought to mislead or else didn’t try very hard to avoid it. My sense is that there’s a different, more likely explanation. Part of the problem in many of these church cultures was that very few of them had a thick enough theology or a confident enough eccelesiology to avoid a kind of panic when the culture around them turned aggressively toxic.

IKDG seemed right for the moment partly because it accurately perceived it. Harris argued that intimacy was the reward of commitment, not simply the “next step” on a scripted cycle of whenever, whoever sitcom romance. Harris argued that sexual intimacy takes a part of you with it; the crisis of teen pregnancy shouted in agreement. Harris argued that the family had a crucial role to play in romance. He was right, and the brutal, abusive, and family-less landscape of Woodstock 99 proved him right.

To stand in 2021 and look at evangelical purity culture in the 1990s is to see not just a different church culture, but a much different American one. We are in the great sex recession. You are far more likely to see a trailer for a comic book movie than a gross-out comedy. Woodstock 99 is very, very far away. The legalistic ethos of that bygone era is unfathomable today, but part of the reason is that the cultural context that made it plausible is also unfathomable. The gospel transcends time, but Christians cannot.

I’m very grateful that many evangelicals have recovered the gospel in a way that was lost back then. I’m very grateful that the experiences of women are being heard in a way they were not back then. I’m very grateful that we are talking about bodies, not just souls, and that the epidemic of online pornography has driven us to talk about guarding the heart, not just our wardrobe. These are all good things. But it is inevitable that in 20 years, someone will perceive in our current efforts a major blind spot, and perhaps even victims of it. We will be judged. Our retelling of our stories should be marked by the humility that comes from this realization.

PS: today even my woke and very secular students are often not involved in relationships! Christian students at university often have a terrible time but today abstinence is often what they have in common with non-Christians!

Liked it then and like it again now. Purity culture was of course totally Arminian in context and sold a false theology: in essence that good behaviour would lead to happy marriage and great sex. Nowhere in the New Testament does God promise that kind of reward for following his precepts. My godliest cousin gave the best years of her life to being an indescribably brave tentmaker missionary in an exceedingly dangerous majority Muslim nation. She remains single to this day although she always would have preferred to have been married. I was widowed comparatively young - my late wife is probably the best Christian I will ever have the privilege of knowing this side of eternity. Theology matters - God is not a slot machine.