When Bots Write Your Love Story

"Is the Internet Real Life?"

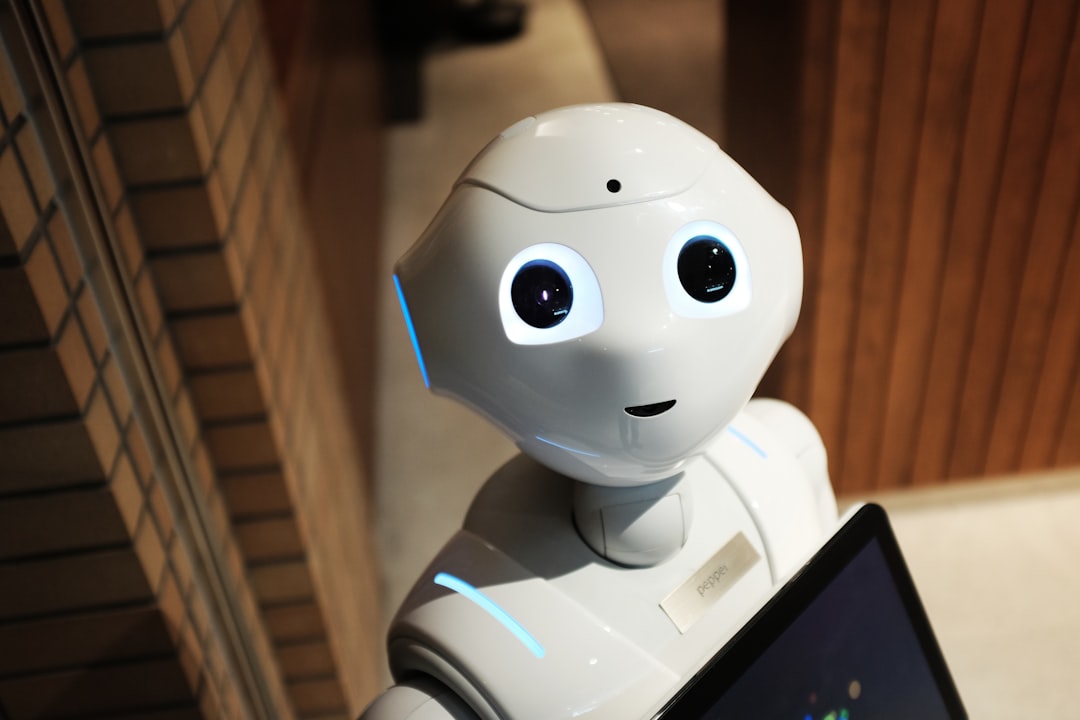

You may remember a story a few years ago about the “affair dating” site Ashley Madison: specifically, the revelation that the site employed a large number of artificial intelligence “bots” that posed as real women looking to hook up. This Fortune piece is partially paywalled, but the most important info is this:

The bots …